Speech Is More Than What is Said or Conveyed

Texas courts' analysis of what counts as a content-based restriction on speech suffers from a fatal philosophical flaw.

From Citizen Lane:

In the philosophical analysis of language, the basic unit is the “proposition.” Suppose for example you take two speakers of two different languages, an English and a German speaker, and have them read aloud, each in his or her own language, the following phrases:

Fire is hot

Feuer ist heiß.

Each of them, despite uttering a linguistically different statement, nevertheless asserts the same “proposition,” or a predication of the property “… is hot” to the subject “fire.” This is because the different terms, e.g., “fire” and “Feuer” nevertheless pick out the same sorts of things in the concept’s extension, namely, an active combustion.

This proposition is at once apparent in the state of affairs and yet transcendent. It requires no particular instantiation (we may say it in any language, for example). But it also need not even require linguistic description. For example, one may indicate that fire is hot by pointing at the fire and shaking one’s hand to indicate pain or avoidance, thereby affirming the proposition “fire is hot” without ever even referencing the linguistic terms fire or hot.

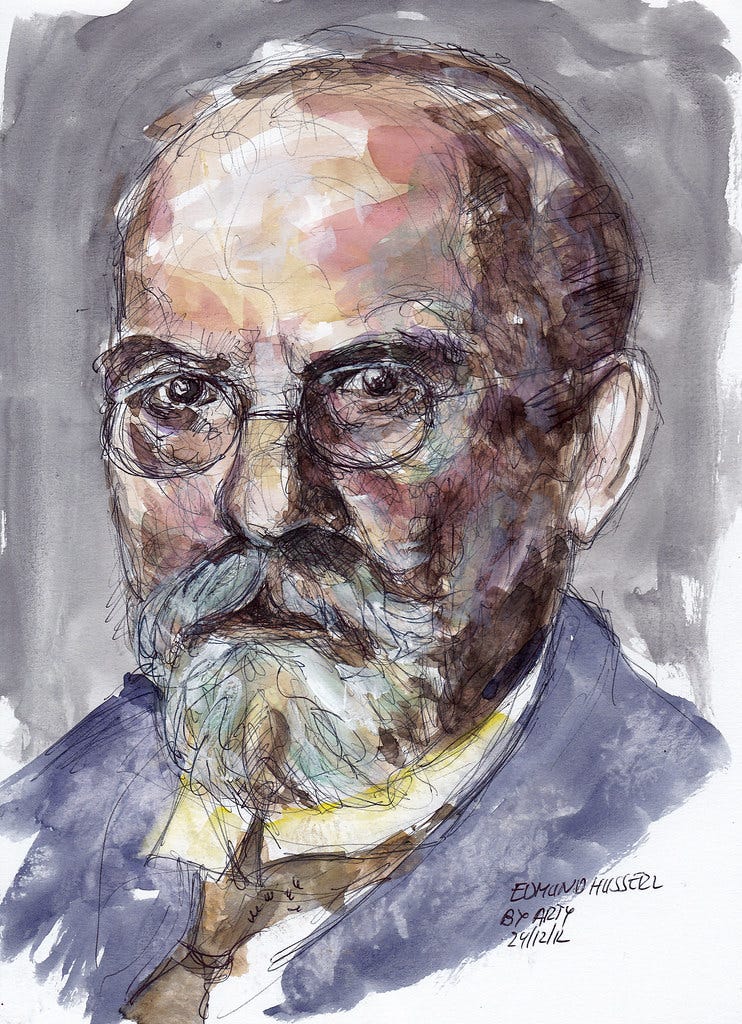

In the continental tradition of philosophy, the thinker Edmund Husserl called this the latent surplus of meaning that arises in all communicative acts. There is more meaning found in the relation of speaker-speech-listener than is literally conveyed by speech, speech acts, or communicative actions. That is, human meaning is never solely confined to the concepts utilized in communication, both verbal and non-verbal, but is also found in relation to the intended audience, the context in which the concepts arise, and attendant perceptual acts. For example, my non-verbal warning about fire’s dangerous properties makes sense only in the situation where I can point at fire or a representation of fire in order to convey the subject of my later warning.

We dallied briefly in the philosophy of language and communication only to set up a larger point, which is to delve, philosophically, into the idea that there can be communicative conduct which is not, in some form. “speech” as defined by the law, apropos of absolutely nothing at all significant this week, nope, nada, nothing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Defending People to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.